New Ideas, Old Materials

Across Latin America the youth voice is largely one of resistance and protest. Many of the publishing projects discussed were born out of social movements. Young people also find it very difficult to get published by traditional publishing houses, which tend to focus on more established, well-known authors. The region’s cardboard movement has been a major outlet for sharing the youth voice. Libros cartoneros (cardboard books), are handmade books, bound in recycled cardboard. They first appeared in Argentina in the early 2000s and have since become popular throughout Latin America. They are published by small, independent presses, sometimes subsidized by the government, with the goal of promoting writing and making literature more accessible. The intent, explains Ecuador’s Freddie Alaya, is not to compete with the traditional book distribution model. “The main interest is political. It’s a way to give an answer to social needs.”

Thinking Beyond the “Book”

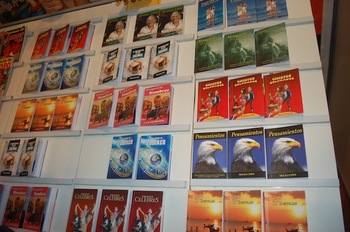

Other examples of strategies for sharing young writers’ work in Latin America rest on a re-thinking of the concept of the book. While the ebook market is evolving, young writers are also developing new conceptions of the physical book to appeal to their market. Dario Cemino from Argentina tells of one young writer who released his “book” of poetry like a pack of cigarettes with each poem rolled on a piece of paper. “We work with the book as an object, a work of art, “says Mexico’s Manuel de Jesus. Thinking of the book as an art piece can help to attract attention and reach new audiences.

Creating New Distribution Channels

Getting into traditional bookstore channels can be difficult for young authors, especially those who choose to self-publish. Creating new distribution spaces for books can provide a valuable outlet and help to build and retain an audience. For Argentina’s Dario Cemino, alternative bookstores are an important ally for young writers.

Cemino’s La Libre bookstore carries a diverse range of titles from Argentina’s growing self-publishing community, allowing young writers a space where their voices can be heard and they can create a community.

Cemino also recommends a more human approach to bookselling. While the traditional model of selling books through stores separates the writer from the reader, Cemino notes that many young Argentinian authors take the books directly to the reader, some selling books from their backpacks as they move around the city. Argentina’s Independent Book Fair also gives its young authors an outlet for reaching readers.

It’s Not Just About the Money

While the returns from the projects described may be low, they provide an outlet for young people’s views and allow for books that would otherwise be ignored to be published. Chile’s El Hecho De, for example, published a book of poems from inmates based on winning submissions to prison poetry contest. The books were then made and distributed to the prisoners.

“Young literature [in Latin America] is very political,” says Ecuador’s Freddie Alaya. Alaya notes that for many young writers, the motive is not to generate profit, but to give young people a voice in the political conversations. “To create change, you have to have social recognition. [Books] create a dialogue between what is marginal and what is official.”

RSS Feed

RSS Feed